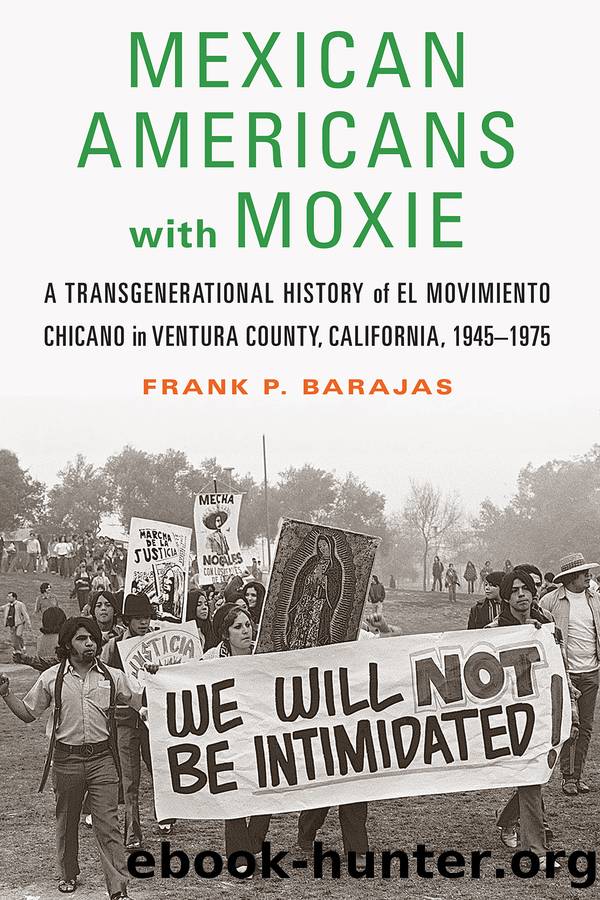

Mexican Americans with Moxie by Frank P. Barajas

Author:Frank P. Barajas [Barajas, Frank P.]

Language: eng

Format: epub

Tags: HIS036140 History / United States / State & Local / West (ak, Ca, Co, Hi, Id, Mt, Nv, Ut, Wy), HIS036060 History / United States / 20th Century, POL010000 Political Science / History & Theory

Publisher: Nebraska

The Rancho Sespe Affair

As part of the Tejano diaspora throughout the nation, in May 1965 Mario Soto and his family of eleven migrated from Mathis, Texas, to work in the citrus orchards of Ventura Countyâs Santa Clara River Valley. The family resided in what Oxnard Press-Courier reporter Bob Denman characterized as a âfive-room shackâ at Rancho Sespeâs Oak Village labor camp. At forty years of age, Mario quit his job in September to further his education in the FWOP. His family remained eligible to remain in the Oak Village camp as his wife, Anita, and son Robert continued to pick fruit in Rancho Sespeâs orchards. After Anita suffered a shoulder injury from a ladder fall, the family received a notice of eviction. The Sotosâ eldest son, nineteen-year-old Robert, became the familyâs main breadwinner and continued to work as a picker until his induction into the U.S. Army in December. This resulted in a second eviction letter, due to the fact that no one in the family worked any longer for the company that owned the camp. Anita, as directed by her doctor, asked to be reassigned to work in a packing shed. The company claimed no such job existed.23

With Lauwerys as their representative, the Soto family asked Rancho Sespe if they could remain at Oak Village for a year; they could pay the monthly thirty-dollar-a-month rent if Anita could work. The familyâs other expenses could be met by the seventy-five-dollar weekly stipend that Mario earned as an FWOP student as well as by the income of Mario and Anitaâs seventeen-year-old daughter Rosita, who worked in a laundry. Company officials refused the request, stating that the housing was needed for workers recruited for the peak of the next harvest.24

The controversy garnered the attention of members of Citizens Against Poverty (CAP) and the Oxnard Legal Aid Association. The Oxnard Press-Courier reported that employees of the Rancho Sespe Company worked as casuals, on a day-to-day basis, and that the end of employment constituted grounds for residents to be evicted.25 Ultimately, the Soto family moved out of the Oak Village camp to live in the neighboring community of Santa Paula; Mario could not chance court costs if he contested the eviction and lost. But the Soto affair demonstrated the precarious nature of farmworkersâ life and work, which offered little security and little freedom.

At an OEO conference in Washington DC, in January 1966, Peake, who represented Operation Buenaventura, and Lauwerys, who represented the FWOP, underscored the larger import of the SotoâRancho Sespe dispute, as it signified the serf-like status of farmworkers. In a further restriction on their independence, farmworkers at sites such as Oak Village could not join a labor union without the threat of termination and concomitant eviction. In turn, the children of farmworkers experienced instability as the security of their residence rested on their parentsâ good standing with the company.26 To remedy this modern form of feudalism, Peake and Lauwerys recommended that the federal governmentâs Farm Home Administration (FHA) establish grants to public and nonprofit agencies to develop farmworker housing.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Africa | Americas |

| Arctic & Antarctica | Asia |

| Australia & Oceania | Europe |

| Middle East | Russia |

| United States | World |

| Ancient Civilizations | Military |

| Historical Study & Educational Resources |

Cat's cradle by Kurt Vonnegut(15340)

Pimp by Iceberg Slim(14490)

4 3 2 1: A Novel by Paul Auster(12378)

Underground: A Human History of the Worlds Beneath Our Feet by Will Hunt(12091)

The Radium Girls by Kate Moore(12020)

Wiseguy by Nicholas Pileggi(5772)

The Fire Next Time by James Baldwin(5433)

Perfect Rhythm by Jae(5399)

American History Stories, Volume III (Yesterday's Classics) by Pratt Mara L(5302)

Paper Towns by Green John(5182)

Pale Blue Dot by Carl Sagan(4999)

A Higher Loyalty: Truth, Lies, and Leadership by James Comey(4955)

The Mayflower and the Pilgrims' New World by Nathaniel Philbrick(4496)

The Doomsday Machine by Daniel Ellsberg(4486)

Killers of the Flower Moon: The Osage Murders and the Birth of the FBI by David Grann(4444)

The Sympathizer by Viet Thanh Nguyen(4386)

Too Much and Not the Mood by Durga Chew-Bose(4339)

The Borden Murders by Sarah Miller(4316)

Sticky Fingers by Joe Hagan(4190)